Comparisons of the Covid-19 public-health responses and data from San Juan, Skagit, and Whatcom Counties reveal striking differences that may help these counties and Washington state chart a viable path forward beyond the current crisis.

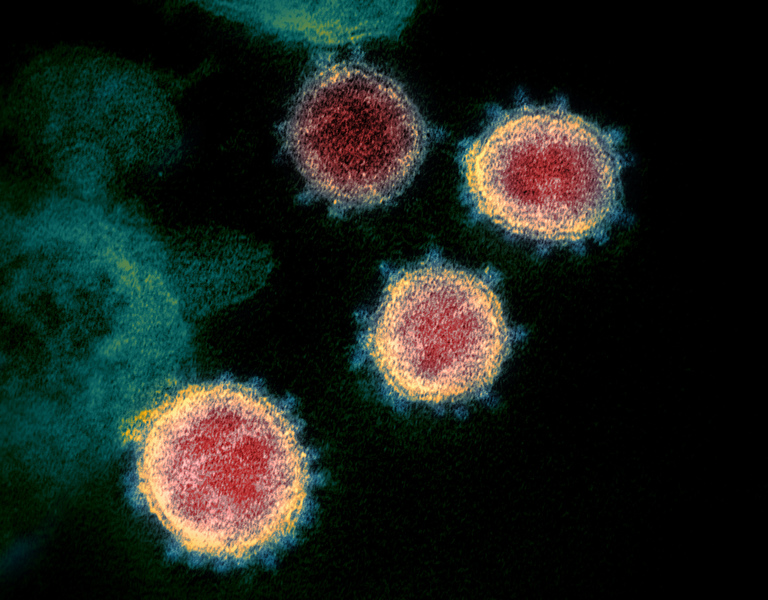

The novel coronavirus SARS-Cov-2 crept northward from King and Snohomish Counties in February, when the possibility of community transmission by asymptomatic individuals was poorly understood. On March 10, both Skagit and Whatcom Counties reported their first confirmed cases.

That same day, what is being called a “super-spreader” event occurred at the Mt. Vernon Presbyterian Church, where the Skagit Valley Chorale was holding a rehearsal that evening. Precautions were taken, including recommendations that members experiencing flu-like symptoms stay home. But “one person felt ill, not knowing what they had,” said Lea Hammer of the Skagit County public-health department. That person “would end up infecting 52 other people.”

It was previously thought that communication of the disease could occur mainly through coughing or sneezing, which would emit large droplets on which the virus could travel up to six feet — or by touching surfaces on which these droplets might have fallen. But an April 1 National Academy of Sciences letter reviewing the rapidly emerging scientific literature suggested that normal breathing could be responsible, too. Ultrafine aerosol particles, able to remain aloft for hours, can cause significant transmission.

The choral-society outbreak put a somber exclamation point on this conclusion. By late March, two of its members had died of the disease. And this pivotal event most likely enhanced the rapid Covid-19 spread throughout northwest Washington.

On Friday, March 20, San Juan County reported its first case of Covid-19 after tests results came in. “The patient is isolated and being treated at home,” noted Public Health Officer Frank James, M.D., in a press release. “County Health staff have contacted a small number of people who have had close contact with the patient. These individuals are being guided to quarantine themselves at home and to monitor themselves for fever and respiratory symptoms for 14 days following their last exposure.”

Asked the following day whether these “close contacts” would be tested for the disease, Dr. James lamented how difficult it then was to get anybody tested, given the scarcity of testing materials and laboratories qualified to evaluate the tests. Washington’s Department of Health, he said, was limiting testing to health-care workers, emergency medical technicians, and individuals over 65 experiencing flu-like symptoms.

Islands residents were understandably concerned, given the aged population and lack of sufficient hospital facilities. Persons who experience life-threatening symptoms have to be airlifted to mainland hospitals, which can take up to an hour.

In a March 23 Orcas Issues posting directed at San Juan County officials, Orcas Island resident Joe Symons wrote, “Please take immediate action to restrict non-resident access to SJC for a minimum of 90 days and make the resolution renewable.”

Similar urgent “stay-away” sentiments were being expressed by island residents on both US coasts worried about “pandemic refugees” using second homes to shelter in place. Indeed, the ferries to Orcas Island were unusually heavily booked on Saturday morning, March 28, three days after Governor Inslee’s “Stay Home – Stay Healthy” order went into effect.

On the mainland, Covid-19 infection rates were soaring. Whatcom County’s confirmed cases reached 139 by month’s end, and Skagit County had hit 128. By April 4 Whatcom County had reported 18 deaths attributable to the disease, due largely to outbreaks at nursing homes and assisted-living facilities, especially Shuksan Healthcare Center in Bellingham.

But the dreaded San Juan County outbreak failed to materialize. Apart from a “spike” of four positive cases reported in early April, at most two cases per day came in. By April 17, the cumulative total had leveled off at only 14, where it remained for the rest of the month and into May. That’s about 85 positive cases per 100,000 residents, compared with current figures (as of May 12) of 311 for Skagit and 149 for Whatcom. And there were — and still are — no deaths at all in San Juan County.

Part of the differences can probably be attributed to better islander adherence to social-distancing measures, given our superannuation and thus much greater chances of dying from the disease.

At Island Market on Orcas Island, for example, grocery clerks have almost all been wearing masks for weeks; customer access is kept limited and all have to wash their hands upon entering. Given the chances of Covid-19 transmission via normal breathing, these health precautions are obviously warranted.

But, based on anecdotal evidence, such measures were apparently not being followed, at least not by mid-April, in Skagit and Whatcom Counties — for example, at the Anacortes Safeway and the Fred Meyer and Haggens stores in Bellingham.

Skagit County numbers have come in higher due partly to its agricultural, retail, and manufacturing industries, according to Kayla Schott-Bresler of its public-health department. “There’s not a lot of telecommuting opportunities if you work for a potato farm or dairy,” she said. “It’s extremely difficult for our residents to stay home, and stay safe and healthy, because of the work that they do.” This observation applies to Whatcom County, too.

A factor working in San Juan County’s favor may be the comparative scarcity of nursing homes and assisted living facilities in the islands. “When people are living and working cheek by jowl in these facilities, health-care workers are going to get sick,” said Dr. James. “Maybe their masks don’t fit well and they get an extra viral dose.”

But the most important factor, he thinks, is the intensive testing program he has implemented, thanks to special permission granted by the state Department of Health. It includes “asymptomatic essential workers” such as home health-care workers, grocery clerks, pharmacy employees, and ferry workers. In all, 907 test results had come back as of May 12, only 15 of them positive. That’s a “positivity rating” of less than 1.7 percent, on par with South Korea. And it suggests that less than 1 percent of the county population has been infected so far.

For comparison, Whatcom County had an overall positivity rating of 9.6 percent by that day — but its testing program has been more limited. Skagit County had a similar rating at first, according to Schott-Bresler. But since late April, when the county began a drive-through testing program and expanded testable categories to include more essential workers and potentially exposed persons, its positivity rating has fallen below 4 percent.

“Covid-19 testing is certainly making a big difference, together with early case identification and isolation of infected individuals,” observed Dr. James. His aggressive testing program, targeted at essential workers likely to be exposed to the disease, helps to identify such individuals before they have much chance to infect others, keeping the case counts down. That knowledge then helps to inform subsequent contact-tracing activities, which can therefore be kept to manageable levels.

There are important lessons here for the entire state.